- 3 July 2025

- Madan G Anand

- 0

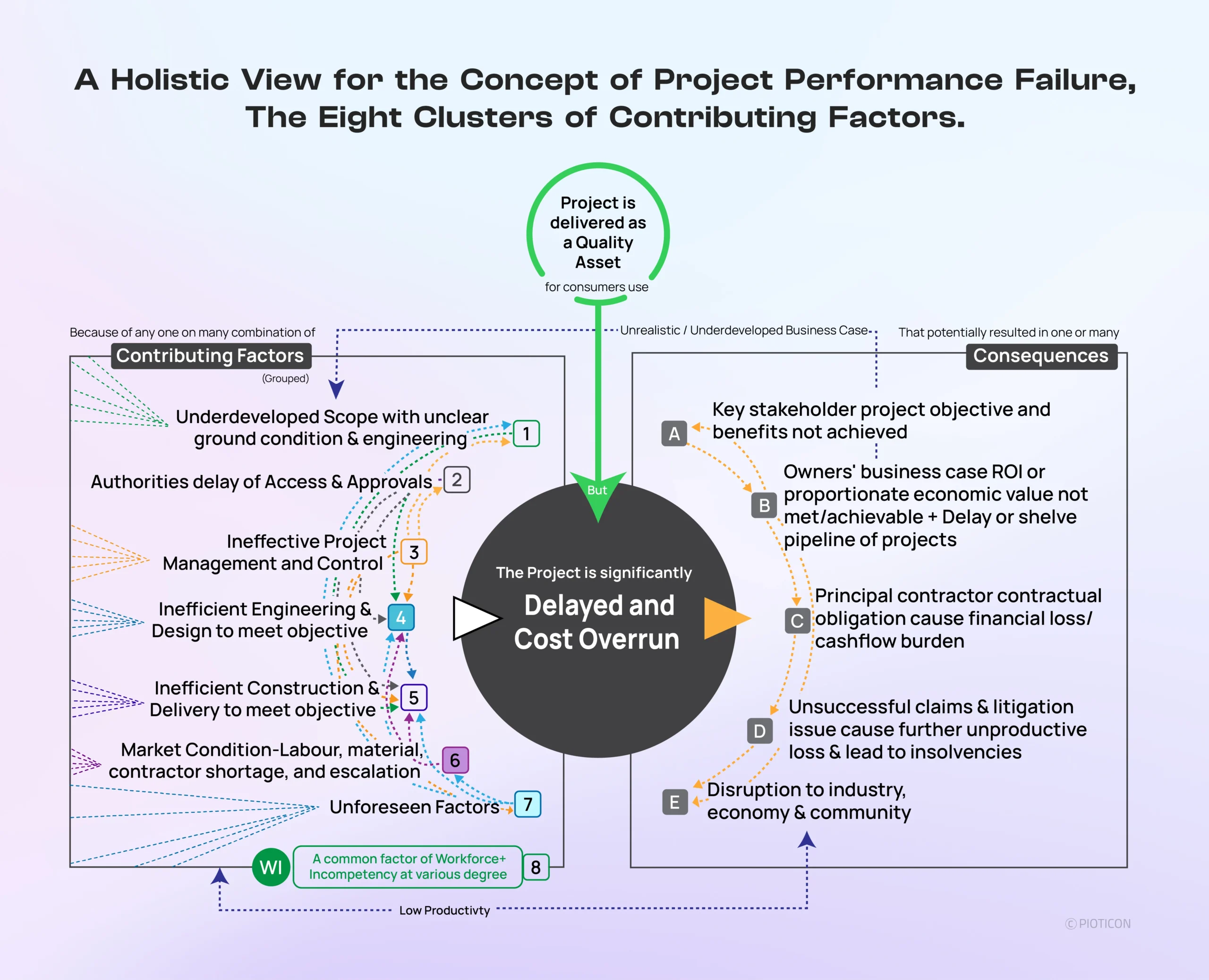

A Holistic View for the Concept of Project Performance Failure

At Pioticon, we don’t just believe in tailored project management, we build for it. Our focus remains on Engineering & Construction projects because they require sector-specific systems, delivery-aligned teams, and capability development rooted in real-world complexity.

We’re not here to offer templates.

We’re here to offer purpose-built systems, tools, techniques and thinking built for the job at hand.

Project failure is often misunderstood. It depends on who looks at it. Success from stakeholder doesn’t mean it is successful from the side of sponsors or owners. The same way, success from owner’s perspective doesn’t mean contractor share the same or vice versa.

Delays, cost overruns, and stalled approvals are visible symptoms of performance failure, but not the cause. These symptoms are frequently discussed in isolation, yet they stem from one consistent issue observed across the industry: productivity.

This edition of the PM² Series presents a holistic view of how major project breakdowns occur, drawing on project delivery processes, market behaviors, award mechanisms, and execution realities, especially across Engineering & Construction projects.

Defining Project Delivery

Project delivery varies not only by size and scope, but by industry type and delivery model, whether portfolio, program, or project. Each operates under a unique objective, stakeholder framework, and complexity profile.

Previously in the PM² Series, we explored how delivery structures and project management differ across sectors. That baseline leads to a critical realization: failures don’t stem from poor intentions or low-quality engineering. They stem from delivery mismatches that appear long before problems are visible on the surface.

Problem occurs depending on decision made at different stages

STAGE 1 – The Starting Point: An Idea and the Business Case Development

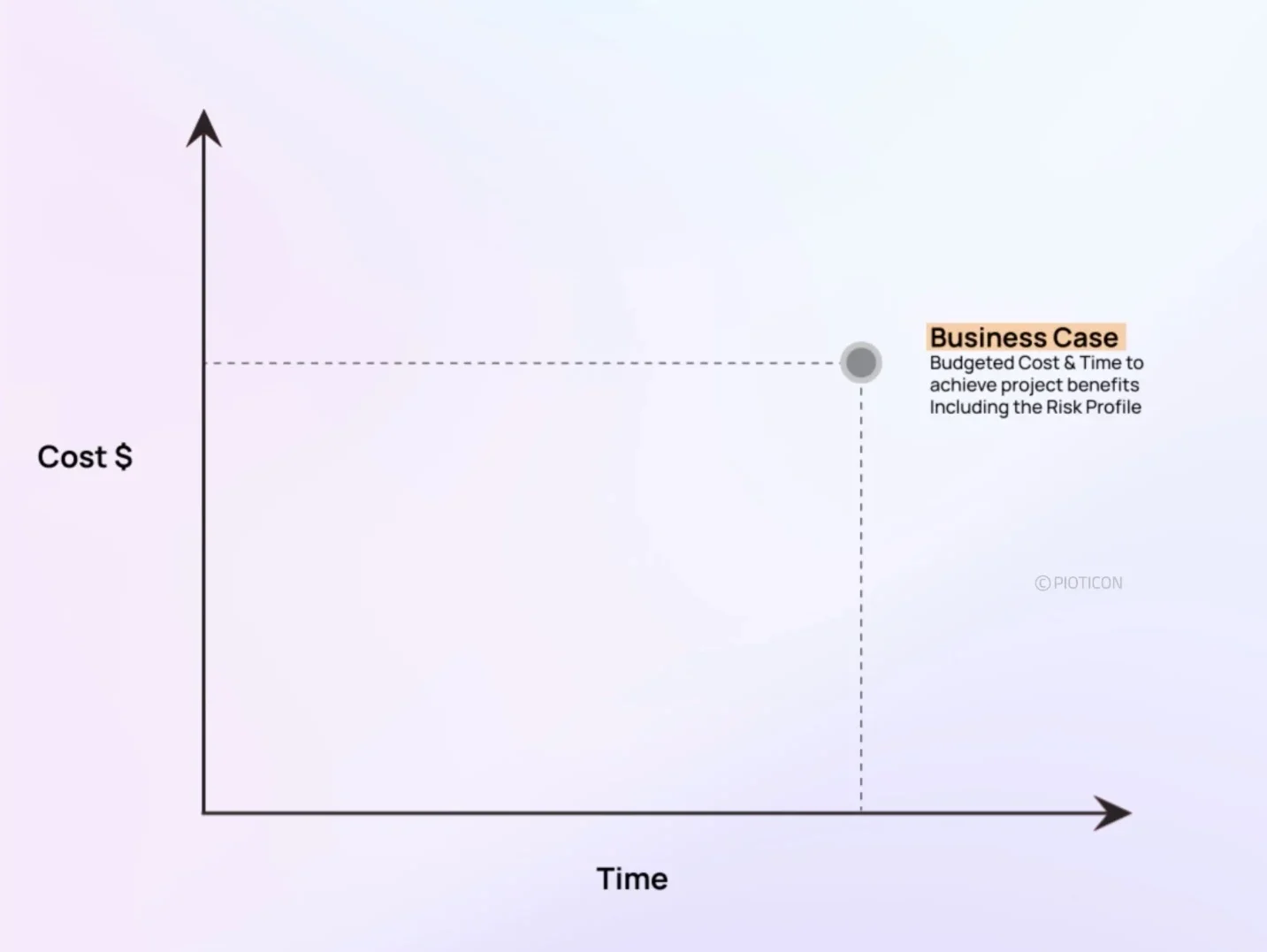

Most projects begin with a need or an idea, and a well-defined business case along with feasibility study. It estimates time, cost, and risk, typically developed with input from experienced professionals using historical data, risk classification (Class 1–5), and defined benefits.

This is the point where decision-makers and sponsors sign off based on a projected value case, often optimistic but framed with the assumption that risk-adjusted contingencies can cover variability. The project is assessed as financially and strategically viable at this stage.

There’s no sign of problem at this stage assuming expert estimate of scope, time, cost & risk is adequate.

STAGE 2 – Defining Project Delivery Model, Market Engagement & Awarding the Program or Project

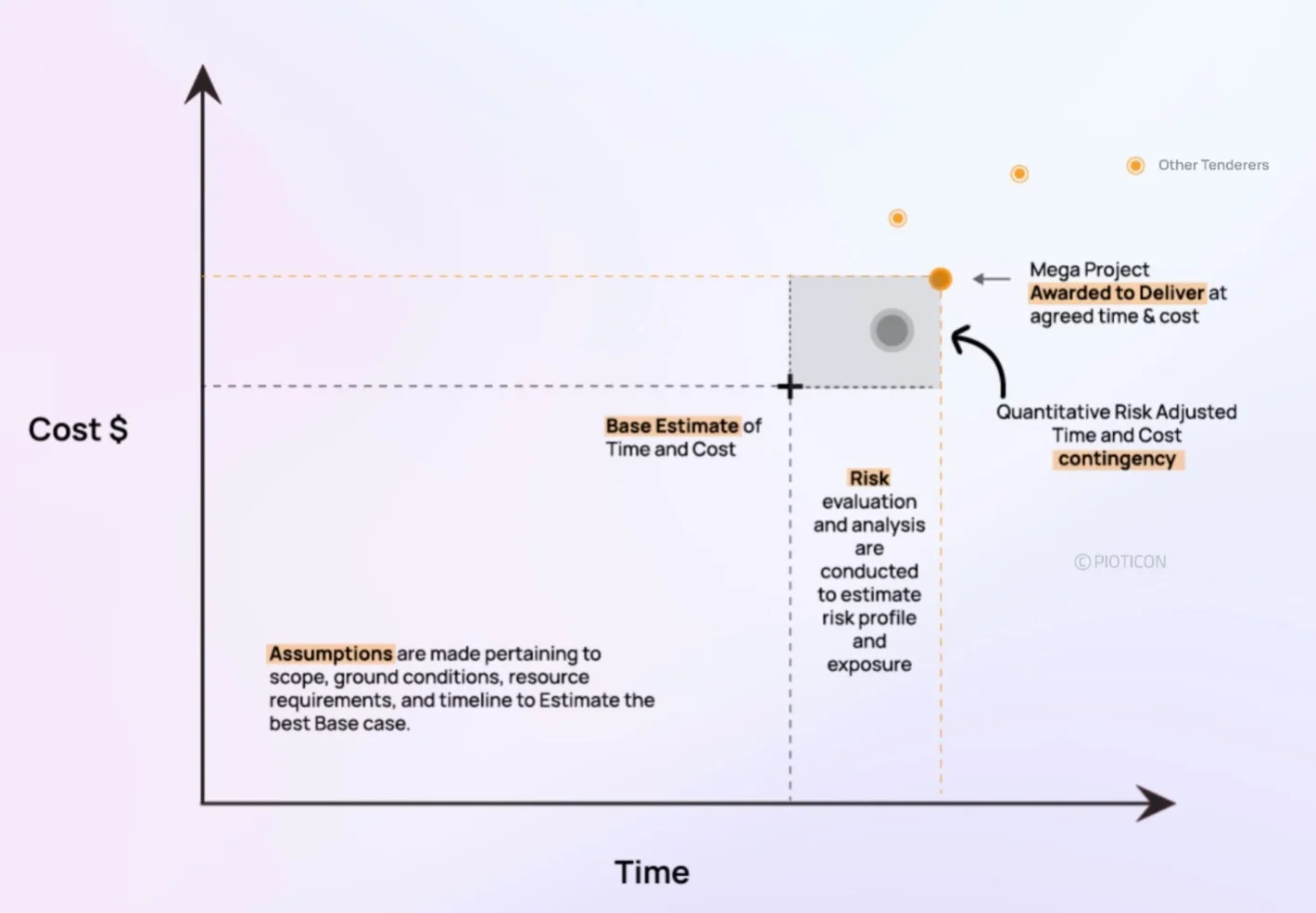

Project or Package of works are decided on which Contractual model (Construct only, Design & Construct, EPCM, Alliance or PPP) is right fit to deliver those projects.

When looked as a combined stakeholder benefits, each contractual model has its own merits and demerits.

Once the sponsor approves the project to go to market the next phase tests the market through design and construct procurement. Consultants and contractors submit proposals based on scope documents, interpretation, and assumptions, each applying their own risk assessments and pricing models. Procurement teams evaluate offers using both quantitative and qualitative measures. Most organizations follow strict administrative policies and compliance protocols. Often, market pricing returns higher than anticipated in the business case. In such instances, clients and sponsors must reassess and either approve increased costs and timelines or repackage the scope. Once awarded, a mega project is expected to deliver against time and cost agreements, but the foundation of that commitment is already on uncertain ground and won’t be visible.

The only sign of the problem at this stage is that if the market indicates anything more time, cost and risk of the same scope.

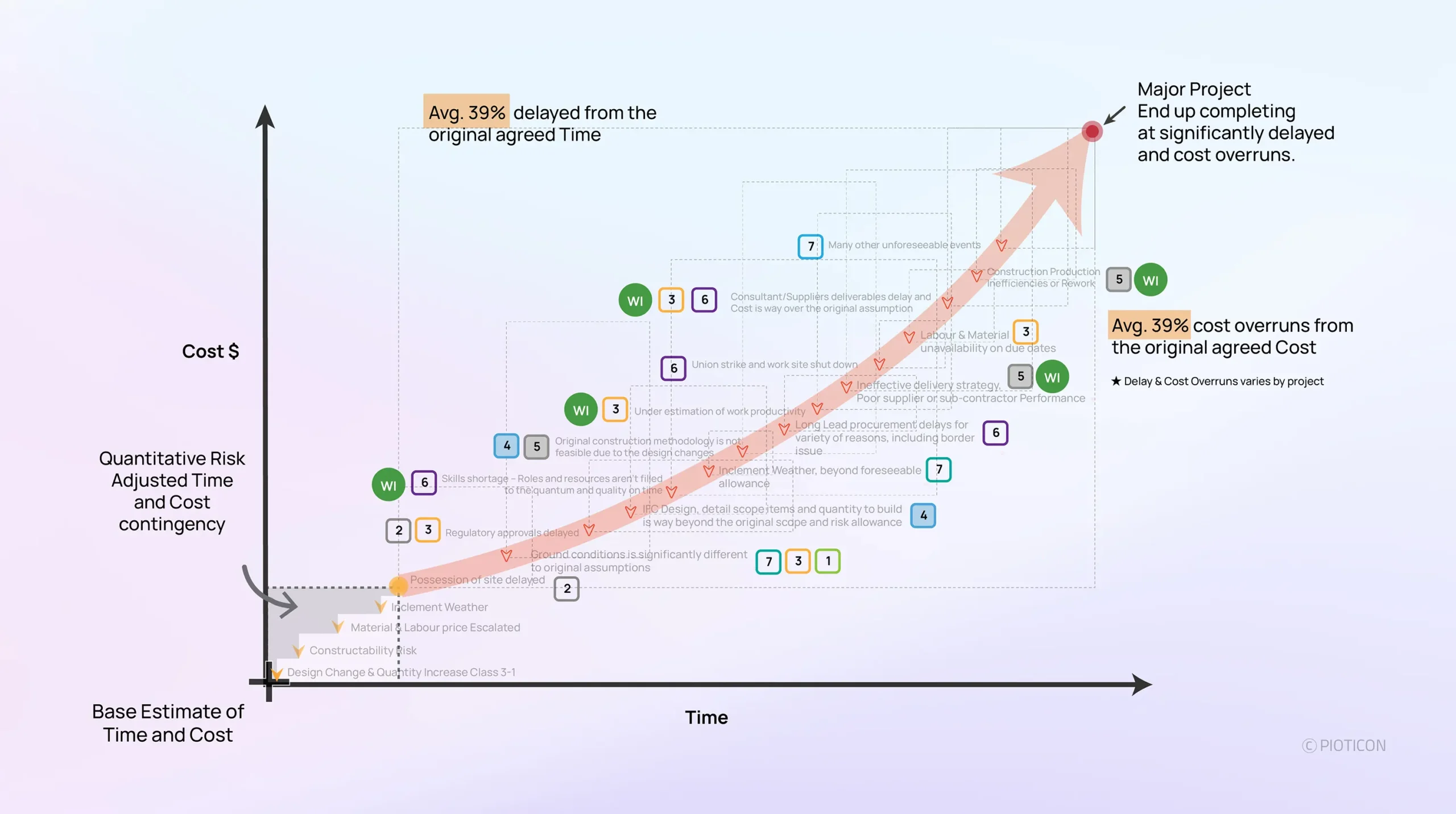

STAGE 3 – What Happens Post-Award Until Design is Complete

The concept scope evolves through various engineering and design stages. By the time the design reaches the Issued for Construction (IFC) stage, the original awarded scope has often changed significantly at the detail scope item and its quantum level, requiring adjustments to construction delivery strategy, time and cost. These changes frequently exceed the risk contingency allowance.

This is the first indication of potential failure stemming from previous stage problems and decisions. Examples include design changes to accommodate ground conditions and specifications, as well as ineffective project management.

However, Contractor often take an over optimised biased decision to recover in construction methodology and efficiency.

STAGE 4 – Construction and Handover post IFC

Classic failure symptoms started coming to the surface at this stage, compounding all the bad decisions made in the earlier stages.

In failed project cases, depending on contractual model, Principal Contractor marry to the high risk project to deliver committed contract with compressed timeline and cost. This environment automatically creates unrest and unnecessary pressure to the team to perform unrealistic output.

In many cases, Estimate at Stage 3(above) also further blows out due to many reasons including ineffective project management, procurement or long lead delays, unproductive delivery performance and unforeseen conditions (weather or ground or market or all combined).

Significance of the Project Performance Failure

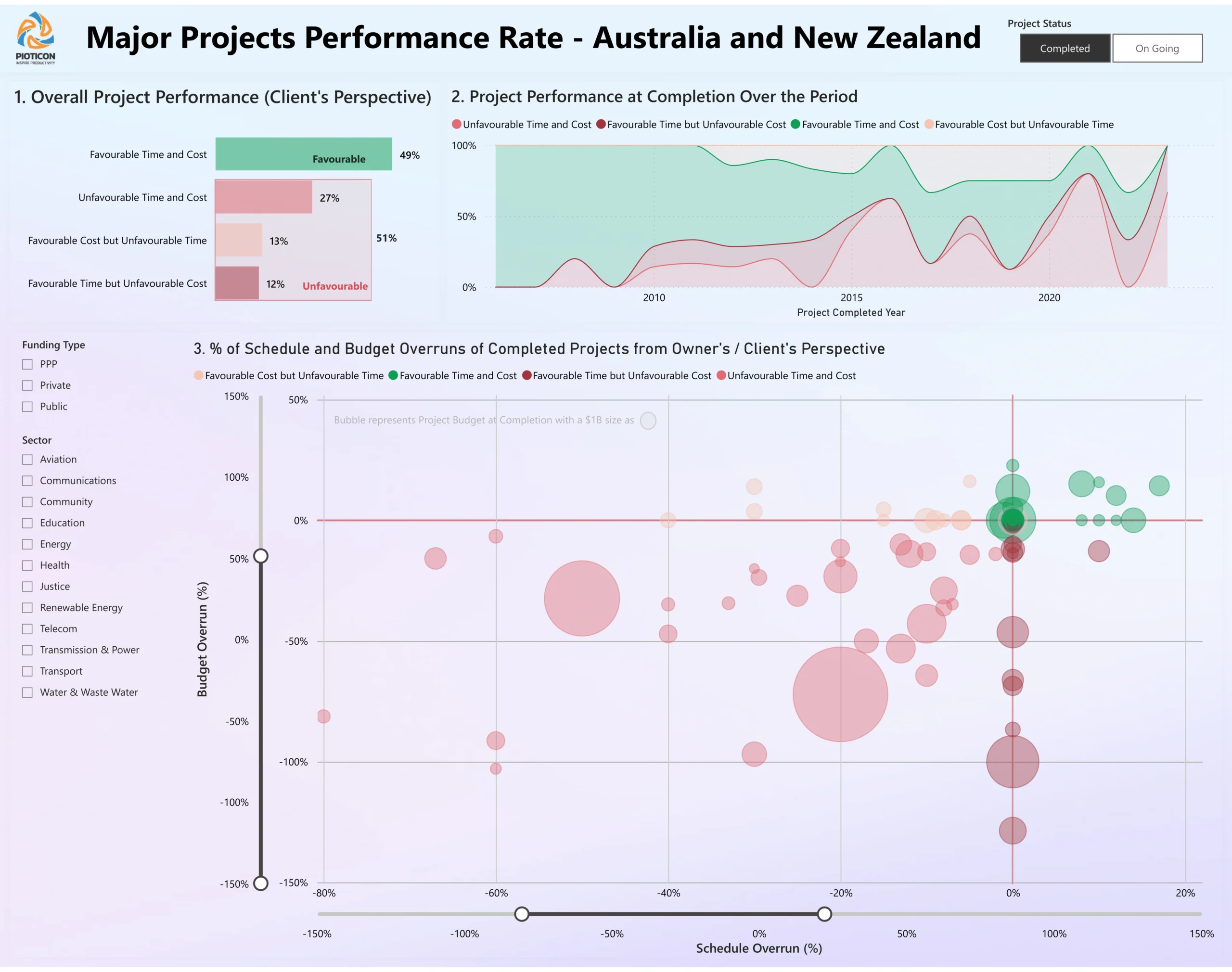

In the case of major project failures in Australia and New Zealand, a clear pattern is emerging. Data shows that nearly 51% of awarded projects deliver unfavorably to Owners compared to original expectations. Even the favorable projects from client/owner’s perspective, contractor might be facing significant loss and not meeting their financial benefits. That is due to the disparity between the contract amount and the contractors’ actual final cost and time.

Depending on the contract model and conditions, it often becomes challenging for the Contractor to recover significant losses through forensic delay and disruption claims.

The full impact on contractors is not always visible publicly, except through insolvency reports or financial disclosures. Big Tier 1 contractors often manage exposures through multi-project cash flow strategies, which mask deeper structural issues in project-by-project reporting. While there are projects that hit targets, those are becoming rare and are mostly legacy examples, not current trends.

Hence, it is not practical to get accurate data points to get true picture, analyse the real root cause and contributing factors in the right significance order.

The fundamental reason is that the As-Built Quantity* multiplied by the Unit Rate per Scope Item* has significantly exceeded the original estimate.

* As-Built Quantity : This includes the total quantity of work actually executed for the scope item — covering not just the permanent work, but also any temporary or remedial works performed as part of delivering the final approved design.

* Unit Rate per Scope Item : This refers to the actual cost rate to construct one unit of the scope item. It comprises the cost composition of all resource inputs, including labour, materials, plant, and subcontractor services used to deliver the unit quantity.

Patterns That Point to the Core Issue

Generally, delays and cost overruns are consistently traced back to three compounding realities:

- The base assumptions were not realistic for the original scope intended for the project objective

- Risk was underestimated or transferred without the capability and capacity to manage it

- Execution systems couldn’t match the complexity

Every layer adds friction. Individually, they are manageable. Together, they become overwhelming.

Despite schedule and budget failures, most infrastructure projects still deliver high construction quality. Engineers and builders should be acknowledged for this. Quality proves that capability exists at a technical level.

Project failures are rarely caused by one factor. They emerge from highly interconnected issues that influence each other throughout the lifecycle. These include:

- Shifting scopes

- Design development lag

- Market pricing pressures

- Resource unavailability

- Delivery model mismatches

- External events

- Inflexible systems

Each factor may seem isolated, but it contributes to overall delivery drift.

A Holistic Picture of Project Failure: The Eight Clusters of Contributing Factors

A review of industry-wide trends shows that challenges group into eight recurring clusters of root issues. These are not fully measurable yet due to data limitations, but they reflect broad causation themes visible across project audits, reports, and real-world execution:

- Underdeveloped scope with unclear ground condition and engineering

- Authorities delay of access & approvals

- Ineffective project management & control

- Inefficient engineering & design to meet objective

- Inefficient construction & delivery to meet objective

- Market condition- labour, materials, contractor shortage, and escalation

- Unforeseen factors

- A common factor of workspace + incompetency at various degree

No single cluster explains all failures. The interdependency between them is what causes delivery to unravel.

Final Thought

Project performance failure transcends simplistic blame narratives. It emerges from a complex interplay of unrealistic expectations, misaligned delivery models, capability gaps, and systemic inefficiencies. While infrastructure projects often achieve world-class technical quality, the persistent gap between promise and delivery remains.

True improvement requires a paradigm shift. Success depends not on fixing isolated factors, but on transforming the entire ecosystem: how projects are conceived, planned, resourced, and executed.

Only by embracing this holistic, systemic perspective can we begin to bridge the critical divide between project ambition and actual achievement, ensuring projects are delivered not just with technical excellence, but within the time and cost frameworks promised.